"Race has nothing to do with this disaster." That sentiment is now

the official story, echoed in press briefings by high-ranking officials such as Condoleezza Rice and in numberless television talk show commentaries. How closely does this official line reflect the reality of what has happened since Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast?

Not surprisingly, there is no smoking gun that proves that the lag time in federal response to the disaster has had anything to do with race. Yet the distressing images and lopsided demographics of those who endured the chaos of post-hurricane New Orleans suggest that the tell-tale significance of race relations inheres in the politics of emergency disaster relief as much as it does in other political spheres like electoral campaigns, voting, redistricting, social security, public education, criminal justice, and, above all, local and federal economic policies. In each of these spheres, "race" is a word that dare not speak its name in contemporary American political discourse, despite its continuing social salience and the undeniable evidence of race-specific economic effects that result from supposedly neutral public policy. The socioeconomic impact of race, in turn, is most clearly revealed to Americans at moments of social crisis, such as that precipitated by the fury of Hurricane Katrina.

When Michael Omi and Howard Winant wrote their seminal analysis of the politics of race in American society,

Racial Formation in the United States (Routledge 1986, rev'd. 1994), their principal task was to offer an archaeology of the concept of race in the face of overwhelming evidence that racial discourse was being driven underground by the "color-blind" agenda of American neoconservative politics. Omi and Winant describe such anamnestic politics, and their meliorative (or leveling) neoliberal counterparts, as the most recent iteration of the kinds of "racial projects" that have marked American history since the nation's inception. They warn of the twin temptations of thinking of race as an

essence ("fixed, concrete, and objective"), or as a mere

illusion, "a purely ideological construct which some ideal non-racist social order would eliminate" (1994:54). They argue that it is necessary, instead, "to understand race as an unstable and 'decentered' complex of social meanings constantly being transformed by political struggle" (55).

The only antidote to racism, Omi and Winant insist, is to "notice race" and thereby to "challenge the state, the institutions of civil society, and ourselves as individuals to combat the legacy of inequality and injustice inherited from the past" (159). The images flickering across TV screens since August 29th, when Katrina barreled ashore, were belatedly acknowledged by the corporate media as reflections of a deeper political history of the US and, in particular, of the American South. That history is shaped by racial projects that consist of shifting cultural representations and economic structures. It is as absurd to erase this history as it is to ignore the racial elements of the catastrophe in New Orleans still unfolding before our stunned eyes. While racism in its crudest and most essentialistic form may or may not have tainted the official response to the New Orleans debacle, the aftermath of the storm requires an analysis of race that would help to explain why an extraordinary number of those who were most severely affected are African-Americans; how official relief was meted out among the survivors in direst need; and how the American public at large has reacted to these devastating images and to the unpardonably slow rescue efforts.

A time-line of official responses to the disaster, which suggests the magnitude of federal ineptitude or disregard, can be found

here.

Among those who have focused on race as an element of the disaster most in need of explanation is Anya Kamenetz, a freelance author who grew up in New Orleans. She argues in a

Village Voice editorial,

"My Flood of Tears," that race has played such an enormous role in the unfolding of events because for New Orleans, more obviously than elsewhere, race is not just a central element of the city's history. It also warps the city's present conditions insofar as the spoils of a racist history are still vastly unevenly distributed.

In a similar vein, Dan Rabinowitz of

Haaretz reminds his readers that

"catastrophes don't just happen." Rabinowitz sharply admonishes those who refuse to acknowledge the ideological roots of this disaster:

It is impossible to understand [the collapse of order in New Orleans] without relating to poverty and racism. Black people, most of them poor, constituted 68 percent of the population of New Orleans until Katrina arrived, and it was natural that the vast majority of the people without cars who were stuck in the city were black: a weak and weakened population, full of bitterness after generations in which they were abandoned to poverty, ignorance and crime. For these people, the police, the federal authorities, the supermarket chains and the department stores are the enemy. They looted food in order to survive, and took electrical appliances, clothing and shoes to return to themselves, on the backdrop of the disappearing city, something of what White America has always denied them. The social collapse of New Orleans is the shameful fruit of the ideology of "every man for himself," and of the budgetary and political policy — of each individual city and county — that derives from this.

Rabinowitz's biting commentary effectively sums up what I and others have found so shocking about the terrible events themselves and their representation in the corporate media. What is painfully evident to media watchers like myself and to many of the most incisive public editorialists is that the material history of the Katrina tragedy begins long before the end of August. President Bush and his administration, as many have pointed out, began dismembering FEMA in his first term, despite earlier efforts by the Clinton administration to restore the agency to the fiscal health of its earlier years. This was part of the relentless "starve the beast" policy of reducing vital government services for poor and working-class Americans while cutting taxes for the wealthiest citizens.

But the problems that turned this natural catastrophe into a societal tragedy go beyond these specific policies and this particular political moment. The responsibility for the grinding poverty of so many New Orleaneans cannot be laid at the feet of a single administration or even a specific political program. The roots of economic inequality in New Orleans, intertwined as it is with the legacy of racist American politics and policy, are planted much deeper in our national history than the major media is generally capable of acknowledging, let alone discussing in any depth. Television snippets and newspaper reports simply cannot adequately address this long, complex, and sordid national experience. And yet, a comprehensive analysis and redressing of this history should not be the task of academics and political activists solely. What is needed is a broad public discussion of race and class as fundamental American concerns in the 21st century — concerns that touch upon the many different layers of public policy, socioeconomic structure, resource distribution, and cultural production. In the absence of such a discussion, the nation will continue to be haunted by its past and unable to critically evaluate its present.

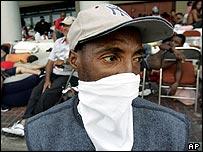

Image: a black man "looting;" white people "finding."

Image: a black man "looting;" white people "finding." (Click on the image above for a larger view.)

Post script:

The Onion offers a humorous take on some of the concerns I've addressed here, including issues of race, in a spoof,

"God Outdoes Terrorists Yet Again."News reports today indicate that Cuba has offered to send 1000 doctors to the hurricane stricken region, and that countries such as Bangladesh ($1m), Venezuela ($1m to the Red Cross), Djibouti ($50k), Azerbaijan ($500k) and Gabon ($500k) are offering emergency aid. That's of course to return the favor of US foreign aid largesse, which in terms of percentage of GNP is the lowest of any industrialized nation in the world.

—Lincoln